Three Act Story Structure (Including the Seven Key Plot Points Your Novel Needs)

Does your novel draft feel a little lopsided?

Is your pacing off, or does it seem like the story takes ages to get started? Maybe the tension slackens off in the middle, or you feel like something big needs to happen – you’re just not sure what (or when).

Here’s the good news. Most writers will have an innate grasp of the three act story structure. We’ve all read plenty of stories, after all—and seen stories on the screen. (Movies tend to follow a very precise story structure, often down to the minute.)

So your story is probably already coming close – but your sense that something is “off” suggests the structure needs a bit of tweaking.

We’re going to go through the most basic story structure out there, the Three Act Structure, then dig in a bit deeper with some specific plot points that fit within that structure.

Book recommendation: If you want lots more detail on structure, particularly on how specific plot points work, K.M. Weiland’s Structuring Your Novel is an excellent, detailed, and well-informed read.

What is the Three Act Structure?

The three act narrative structure is often associated with Hollywood and screenwriting – but the basics of it date back to Aristotle. It’s an easy template to use: each story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. These are sometimes called the setup, confrontation, resolution.

You’ll see this structure not just in stories but in nonfiction work too: if you write blog posts, for instance, those will have an introduction (beginning), a main body (middle), and an end (conclusion).

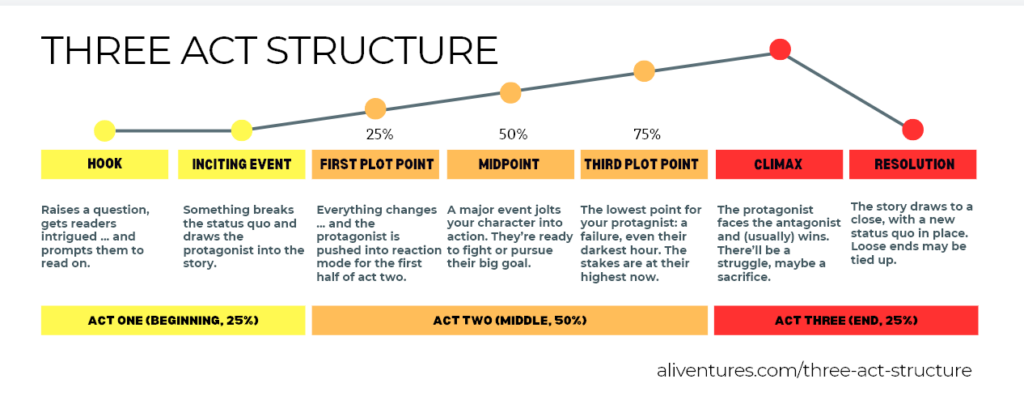

The first, second, and third acts aren’t all the same length. With a novel or film, the first act will usually be around 25% of the story, the second act will be 50%, and the third act will be 25%.

Here’s a quick look at how those three acts work within the story:

Act One (First 25%)

Act One introduces us to the protagonist and the main characters in their ordinary world. We’ll get to see the protagonist’s “status quo” – their normal life (or at the very least, it’ll be implied). There might already be some sense of tension or disruption within that, though … and before long, something irrevocable will happen to thrust the protagonist out of business-as-usual and into the action of the story.

The first act is likely to raise unanswered questions to keep us reading, and it’ll usually introduce us to the antagonist or antagonistic force of the story.

Act Two (Middle 50%)

By the start of Act Two, the story is fully underway. This middle section of the book is characterised by “rising action”. The story is getting more complicated, the stakes are getting higher, and the protagonist is forced to change and grow as a result (moving forward on their character arc).

Usually, the character will spend the first half of Act Two in a reactive mode. They might be panicking, trying to move forward toward their goal but struggling, or not really seeing their situation clearly. At the midpoint, which we’ll come to in a moment, everything changes. The protagonist sees the conflict more clearly – and they begin to act rather than react.

Act Three (Final 25%)

In Act Three, everything gets resolved – for good or for bad. The tension in the novel builds to a climax, where the protagonist confronts the antagonist (or the antagonistic force). After this climax, we have “falling action” – the major conflict has been resolved, and now the story draws to an end.

If this book is part of a series, there may be a further “hook” at the end to encourage us to read the sequel, and some issues raised in the story may not be resolved.

Where Do Key Plot Points Fit Within the Three Act Structure?

We’ve mentioned a couple of important plot points, like the midpoint and the climax of your story. You’ve probably come across other key plot points too – such as the “inciting incident”. But how do these fit into the three act structure?

I’ve created this diagram to help. It doesn’t show every possible plot point (for instance, you might add “pinch points” in between the plot points – these are where we get some kind of reminder of the antagonist’s power). But it shows the major plot points and how they fit with the three act structure.

You can use these plot points within a short story, as well as within a whole novel. Here’s how they work in a little more detail, with examples from The Hunger Games.

Hook (Start of Act One)

The hook comes at the start of Act One, within the first few pages of your story. It could be the opening line, but doesn’t have to be. Your hook might not be a huge thing (like a dead body or an alien invasion) – just something that raises a question, intrigues readers, or makes them want to read on.

Example:

In The Hunger Games, the initial hook is the line “This is the day of the reaping” in the first paragraph. We’re immediately intrigued and concerned: what is the reaping?

Inciting Incident (Middle of Act One)

Early on in the story, something needs to happen to set the story in motion by breaking the status quo. This will usually be in the first half of Act One, probably around 6%–15% of the way through the story.

This is called the “inciting incident”, “inciting event” or sometimes “the call to adventure”. (Some writers feel the call to adventure is a separate but related point.)

Example:

The story of The Hunger Games really kicks off when Katniss volunteers to take the place of her younger sister Prim at the reaping. The moment where she shouts “I volunteer as tribute” sets everything else in motion.

First Plot Point (Start of Act Two, 25%)

The first plot point comes around 25% through the story. It’s a moment where everything changes: the setup phase is over, and Act Two is beginning. Your protagonist is going to spend the next quarter of the book reacting to the change and its implications.

Example:

In The Hunger Games, the first plot point is when Haymitch begins coaching Katniss and Peeta, and when their training begins. We see Katniss in reactive mode – mainly doing what she’s told and what’s expected of her, and feeling intimidated by the size of the other tributes.

Second Plot Point or Midpoint (Middle of Act Two, 50%)

The midpoint of your novel comes – unsurprisingly! – roughly in the middle. This is where something major happens that jolts your character out of “react” mode and into action. After this turning point, they’re going to be actively fighting for something, whether that’s for a return to the status quo, or for a goal they’re determined to pursue.

Example:

Katniss is injured in the Games and she’s already seemed on the verge of giving up a few times, before being attacked by the tracker-jackers – but now she meets Rue and forms an alliance. This is where everything changes, and Katniss starts to be much more proactive. Or as she puts it in the narrative, very near the end of Chapter 15:

“And for the first time, I have a plan. A plan that isn’t motivated by the need for flight and evasion. An offensive plan.”

Third Plot Point (End of Act Two, 75%)

The third plot point normally marks a low point for your protagonist – perhaps even a failure, or their darkest hour. Things won’t have gone their way, no matter how hard they’ve tried, and they might feel tempted to give up. But this is where their character development pays off: in the aftermath of this plot point, they’re newly determined to reach their goal. This is often the point at which the stakes are highest, leading into the climax of your novel.

Example:

Katniss is injured in a fight with Clove, and it looks like Clove might be going to kill her – but then her caring for Rue earlier in the story pays off, as Thresh (from Rue’s district) kills Clove and lets Katniss go.

Climax (Middle of Act Three)

The tension in the story builds to a climax: the point where the protagonist faces the antagonist (or antagonistic force). Usually, the protagonist will win – though not without a struggle and quite possibly not without some kind of sacrifice. The climax is the moment that the rest of the story has been leading up to, and it needs to be engaging and satisfying.

Example:

The climax of The Hunger Games is when Katniss and Peeta win the games together. When they’re told there can only be one victor, Katniss says they’d rather die together (using poisonous berries) – but Seneca Crane stops them and declares them both victors. It’s a moment of triumph not just in the arena, but against the Capitol.

Resolution (Second Half of Act Three)

Stories don’t normally end with the protagonist striking the final blow against the villain. The final act will carry on after the climax with a “resolution” or “denouement”, showing the new reality (good or bad) sinking in, along with the implications of it. This is where loose ends often get tied up. Sometimes, this also means setting up room for a sequel.

Example:

Both Peeta and Katniss’s wounds are treated and they return to District 12 as victors. There’s still tension though: Katniss has to keep up the pretense that she’s madly in love with Peeta, to convince the Capitol that the suicide pact was an act of adolescent love, not an act of defiance against them. Katniss now realises that in the arena, only she was at risk; now, everyone around her is. This sets up the action for the rest of the trilogy.

Strong Structure is Crucial for a Satisfying Story

Using the three act structure with plot points at specific percentage marks can sound a bit like writing by numbers … but even if you’ve never heard of them before, you might well find you’re naturally hitting these points in your stories.

You don’t need to count your pages and time your plot points at exactly the 25%, 50%, and 75% marks, but if they’re way out, your story is probably dragging in places.

At the planning stage of your novel, the three act structure and major plot points are a handy way to make sure you’ve got key events happening in roughly the right places.

If you’re more of a “pantser” or your writing process tends to be more organic, you might want to brainstorm a few ideas around these major plot points, without necessarily worrying how everything is going to fit together.

When you’re editing, the three act structure and plot points can help you shape your story and see what might need to be cut or moved around.

If you feel that your story is lagging, or that the tension dissipates rather than builds towards the end, then it’s worth looking at the way you’ve balanced your story between the three acts, plus the positioning and nature of your plot points. Tweaking this could make all the difference.

About

I’m Ali Luke, and I live in Leeds in the UK with my husband and two children.

Aliventures is where I help you master the art, craft and business of writing.

Start Here

If you're new, welcome! These posts are good ones to start with:

Can You Call Yourself a “Writer” if You’re Not Currently Writing?

The Three Stages of Editing (and Nine Handy Do-it-Yourself Tips)

My Novels

My contemporary fantasy trilogy is available from Amazon. The books follow on from one another, so read Lycopolis first.

You can buy them all from Amazon, or read them FREE in Kindle Unlimited.

0 Comments