When Dialogue Gets Weird: Representing Unorthodox Forms of Speech on the Page (Text Conversations, Psychic Communication, etc)

Whether you’ve written any fiction yet or not, you’re probably extremely familiar with how dialogue appears on the page: it’s surrounded by quotation marks.

Even if you’re not quite confident with all the finer details of formatting spoken words on the page, it’s probably perfectly natural to you to wrap these words in quotation marks. You likely don’t think twice about it, although this isn’t actually the only option you have.

“Standard” dialogue is, generally, represented in one of three ways:

Type #1: The Most Common Style for Novels and Short Stories

“Excuse me,” John said, “is this the train for London?”

“Yes, though it’s the all stopper,” Daniel said.

Type #2: Standard Format for Scripts, Occasionally Adopted by Novelists / Short Story Writers

John: Excuse me. Is this the train for London?

Daniel: Yes, though it’s the all-stopper.

Type #3: Used in Some Literary Fiction, Particularly Short Stories

– Excuse me, John said, is this the train for London?

– Yes, though it’s the all stopper, Daniel said.

(Type #3 takes some getting used to, and personally, I’m not entirely sure what benefit it has over standard quotation marks … other than, perhaps, lending a clear “literary” stamp to the novel or story. You can see it in use part-way through D.W. Wilson’s essay On the Notoriously Overrated Powers of Voice in Fiction or How to Fail at Talking to Pretty Girls.)

Chances are, you’re using type #1, and that’s all well and good.

But what do you do when you want to represent an exchange of words that isn’t quite so conventional as a face-to-face chat?

Maybe your characters aren’t conversing face-to-face, but through a text message conversation. How do you represent written dialogue instead of spoken dialogue?

If you’re writing something with an SF/F slant and you have two (or more) characters communicating psychically, how do you set that out on the page?

Well, there’s no established convention. Different authors do different things (though you’ll find there’s a fair amount of overlap). In this post, I’ll take you through some possibilities … but the key thing to remember is however you choose to represent your unorthodox types of dialogue, be consistent.

#1: Phone or Other Non Face-to-Face Verbal Conversations

I’ll tackle these first as (a) they’re common to all sorts of types of fiction and (b) they’re not very different from face to face speech.

Here’s an example of a conversation that takes place over an intercom, from J.F. Penn’s Desecration:

She pressed the buzzer. There was no response after a minute so she pressed again, holding the buzzer down until the intercom crackled.

“Yes,” a voice said, indolent, as if he had been woken from sleep.

“Rowan Day-Conti?”

“Speaking.”

“I’m Detective Sergeant Jamie Brooke from the Metropolitan Police. I need to speak to you about Jenna Neville.”

“Jenna?” the voice said, suddenly concerned and alert. “Is she alright?”

“Can you let us in please, sir, so we can discuss the matter.”

It’s set out just like normal speech, and that’s what I’d recommend: there’s no need to do anything fancy.

However … when two characters are talking on the phone (or intercom, walky-talky, Skype, etc), this lends itself to a couple of representational complications:

- A call might get cut off, or be inaudible to one person. As with normal dialogue, I’d recommend representing cut-off speech with a dash (–), and someone trailing off with an ellipsis (…).

- You can’t so easily use body language to provide a dialogue beat, as the speakers can’t see one another. You may want to include thoughts, or have verbal indications of how the non-viewpoint speaker is feeling (e.g. a pause, a cough, changing the tone, speed or volume of their speech).

#2: Real-Time Text Conversations (e.g. on Skype, in an Internet Chatroom)

For me, this is where using quotation marks isn’t necessarily the default choice – though it can be a perfectly sensible one, especially if you only have a handful of text conversations in the course of your novel or story.

Option #1: Treat it as Normal Dialogue

The most straightforward method is to treat the text conversation as normal dialogue, but make it clear to the reader (through dialogue tags and dialogue beats) that it’s taking place through text. (For this, I’ve found that “typed” is usually fairly good equivalent of “said”.)

I have quite a few real-time text conversations in Lycopolis, and this is how I handle them:

“How’s the job hunt going?” Seth asked, in Messenger.

“Pretty well. I’ve got one in the bag, I think, just waiting for an email.”

“Good good.”

Mark checked his inbox again, out of habit rather than expecting anything. But there it was, a reply from the job he’d just about met the requirements for. A glance told him all he needed to know. Unusually high number of applications … Thank you for your interest.

He slumped in his chair. There was still one more to get back to him but he doubted they’d even bother replying. Seth was the one person he could confide in. “Actually, I’m getting a bit worried. I thought I’d have something definite lined up by now. Maybe I should’ve stuck it out here a bit longer.”

“No, you did the right thing. You deserve better.”

“It’s just,” he typed, “I’ve not said anything to Hannah yet.”

“About quitting?”

“Yeah. I thought I’d get something else sorted out and then tell her.”

Option #2: Use Italics

If you prefer, you could use italics for the written text, either with or without quotation marks as well. This is how Camille Perri does it in The Assistants:

Lunch today?

Kevin Handsome was g-chatting. By “lunch” he meant heading down to the cafeteria at the same time to buy our lunches, and then riding the elevator back upstairs together to eat separately at our respective desks. In all it was a ten-minute date, five minutes tops of uninterrupted conversation. A minimum of three minutes of palm sweats and me obsessing. What does this guy want from me?

[…]I agreed to lunch. It’s build-your-own-burger day, I replied, to emphasize that I was in it solely for the red meat and unlimited fixings, not Kevin’s company. See you down there.

(Note the slight drawback to the approach here: the narrator (Tina)’s thoughts are also shown in italics, so when I first got to “It’s build-your-own-burger day”, I initially thought that was something she was thinking rather than typing. It’s a small issue, and the next couple of words quickly clear it up – but ideally, you want to avoid anything that jars your reader out of the smooth flow of the reading experience!)

Option #3: Set it Out Like a Script

Another possibility is to set out the dialogue like a script, with the person’s name at the start. C.L. Taylor’s thriller novel, The Missing, features a number of text conversations between two characters using pseudonyms, thus concealing their identity (it quickly becomes apparent who one of them is, but not the other). The book opens like this:

Jackdaw44: Do you want to play a game?

ICE9: No.

Jackdaw44: Not sex.

ICE9: What then?

Jackdaw44: Questions. I’m bored. It’s just a bit of fun.

ICE9: …

Jackdaw44: I take it that’s a yes. OK. First question. Would you rather go deaf or blind?

ICE9: You really are bored, aren’t you? Deaf.

How Grammatical Should Your Text Dialogue Be?

It’s a fairly well established convention that with regular dialogue, you’re not seeking to transcribe how people actually talk – you’re giving a stylised representation of real-life speech.

When it comes to text conversations, though, it’s trickier: you might feel that you should keep these realistic – you’re essentially transcribing what your characters would type.

I take the easy way out here: my characters are an educated, grammatical, slightly geeky lot who tend to text in full sentences. 😉

Unless it’s really important for your characterisation (or possibly your plot), I’d suggest using standard spelling and grammar. With smartphones and predictive text, “txt spk” is rapidly dating, plus it can be distracting and annoying to read.

#3: Emails and Forum Posts

I tend to handle these differently from real-time text conversations, as they’re often longer and they’re not necessarily intended as part of an ongoing discussion. (Arguably, they’re not even dialogue – you might treat them more like including a diary entry or newspaper report.)

Here’s what Nick Hornby does when including email communication in Juliet, Naked:

The first was entitled ‘Your Review’. It was very short. It said, simply, ‘Thank you for your kind and perceptive words. I really appreciated them. Best wishes, Tucker Crowe.’ The title on the second was ‘PS’, and said, ‘I don’t know if you hang out with anyone on that website, but they seem like pretty weird people, and I’d be really grateful if you didn’t pass on this address.’

A much longer email is set out separately from the narrative, like this:

From: Tucker <alfredmantalini@yonderhorizon.com>

Subject: Re: Re: Your Review

Dear Annie,

It really is me, although I can’t think of a good way of proving it to you. How about this: nothing happened to me in a toilet in Minneapolis. Or this: I don’t have a secret love-child with Julie Beatty. Or this: I stopped recording altogether after I made the album Juliet, so I don’t have two hundred albums’ worth of material locked away in a shed, and nor do I regularly release material under an assumed name.

For longer emails and forum posts, I tend to set them apart from the narrative with an extra line break. For very short (one-line) messages, I put them in italics and include them in the normal flow of the narrative.

You may well treat text messages (between people’s phones) in a similar way to emails, or in a similar way to real-time text conversations. Think about how much back-and-forth will occur, and what’s going to work most seamlessly for that.

#4: Psychic Speech

If you’re writing fantasy or sci-fi, you might well run into situations where characters will talk to one another through psychic means – whether due to magic, technology, or a bit of both.

This is where dialogue becomes distinctly tricky, especially if your characters communicate psychically in something more akin to images or feelings than words. (If that’s the case, you might be best off describing the content of their communication in straightforward narrative, rather than trying to turn it into dialogue.)

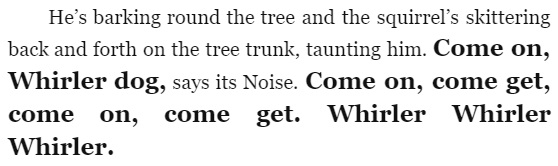

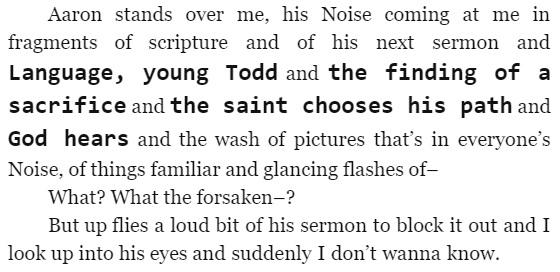

In The Knife of Never Letting Go, Patrick Ness represents (sometimes deliberately, sometimes involuntary) psychic communication with different fonts (my screenshots are from the Kindle version in a browser window, and I imagine the fonts look slightly better in print):

[…]

Here’s what Celia Friedman does in Black Sun Rising, when mixing psychic and regular speech in a single conversation:

Is this what the night is? she wondered. Truly?

She felt, rather than saw, a faint smile cross his face. ‘For those who know how to look.’

I want to stay here.

He laughed, softly. You can’t.

Why? she demanded.

Child of the sunlight! Heir to life and all that it implies. There’s beauty in that world too, although of a cruder sort. Are you really ready to give all that up? To give up the light? Forever?

The darkness withdrew into two obsidian pinpoints, surrounded by fields of cracked ice. His eyes. The dark fae was alive in there, too, and a music that was far more ominous – and darkly seductive. She nearly cried out, for wanting it.

‘Quite, child.’ His voice was nearly human again. ‘The cost of that’s too high, for you. But I know the temptation well.’

Ultimately, as with so many writing decisions … it’s up to you! Ideally, with any form of non-standard dialogue, you want to opt for whatever styling will be as straightforward and unfussy as possible … while keeping things clear.

(If you have scenes mixing, say, psychic communication and out-loud discussion – or a face-to-face conversation while one person is also on the phone – then you definitely need to help the reader keep the different dialogues straight. That could be through different styling of the text or through abundant dialogue tags and beats.)

Do you use any unconventional types of speech in your fiction? Have you read a novel that successfully – or unsuccessfully! – uses text, email or psychic communication? Drop a comment below to let me know about it.

Further Reading on Dialogue

Stylised Talk: Writing Great Dialogue [With Examples]

This post goes through three different examples of dialogue-that-works – all very different. I also go through six key ways to make your dialogue stronger, and cover some key pitfalls to watch out for.

Are You Using “Said” Too Frequently? Dialogue Tags and Dialogue Beats Explained

In this post, I explain why you can probably use “said” more often than you think – and offer ways to change things up with different tags, and with the use of dialogue beats. I also explain some of the finer details of formatting these, particularly in terms of punctuation and capitalisation.

About

I’m Ali Luke, and I live in Leeds in the UK with my husband and two children.

Aliventures is where I help you master the art, craft and business of writing.

Start Here

If you're new, welcome! These posts are good ones to start with:

Can You Call Yourself a “Writer” if You’re Not Currently Writing?

The Three Stages of Editing (and Nine Handy Do-it-Yourself Tips)

My Novels

My contemporary fantasy trilogy is available from Amazon. The books follow on from one another, so read Lycopolis first.

You can buy them all from Amazon, or read them FREE in Kindle Unlimited.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks