Seven Masterful Techniques to Build Tension in Your Fiction (With Examples)

Are you looking to raise the levels of tension in your story?

A high level of tension keeps your story taut, like a wire: it means your reader will be on the edge of their seat as they wait to find out what happens next. It ramps up their emotional investment in your characters, too.

Adding tension is relatively straightforward … and it can really improve the pace of your short story or novel. We’re going to go through seven practical techniques to use, but before that, let’s dig into what exactly we mean by “tension” in a story.

What is Tension in Fiction?

Tension in fiction is the feeling that something bad could be about to happen. It’s that sense you get that a fight’s going to break out, or a character’s on the verge of making a terrible mistake. Tension can build and build as your story progresses, keeping your reader desperately turning the pages.

Tension vs Conflict

Tension is closely related to conflict, though it’s not quite the same thing. Tension is more about how the reader feels: it’s an emotional response. Conflict, particularly external conflict, is about the narrative.

Imagine a scene where an immensely powerful superhero is fighting ten drunk football fans in a pub. There’s definitely conflict in that scene … but if the reader is fully confident the superhero will prevail, there’s not really any tension.

Tension vs Suspense

Tension is also closely related to suspense. Again, I don’t think they’re exactly the same. Suspense is about the unanswered questions of your story: tension is the emotions resulting from all the complications around those unanswered questions.

How Suspense and Tension Work Together to Increase Story Impact (by Tiffany Yates Martin on JaneFriedman.com) is well worth a read if you want to dig further into how suspense and tension work together.

Sexual Tension

If you’re writing romance, or something with a strong romance subplot, you’ll likely also have what we call “sexual tension” in your story. This is a powerful force too and definitely creates forward momentum, keeping readers engaged.

It’s not the type of tension I’m looking at here, but if it’s something you want to get better at writing, How to Build Sizzling Sexual Tension in Your Novel (by Lucy V. Hay on Writers Helping Writers) is a great place to start.

Seven Ways to Build Tension in Your Novel

So how can you increase the tension in your story – especially if you have some scenes or parts of your novel where you feel that there isn’t much dramatic tension?

#1: Give Your Characters Conflicting Values

When two characters have different goals, that often causes conflict (and you can build tension around that).

But having characters with different values can create powerful tension: it’s not simply about two people both wanting the same promotion, it’s about a clash of what each person sees as truly important. This can also feed into internal conflict, where a character may face the dilemma of holding true to their values vs giving in for an easier life.

Example:

Like most gunters, I was horrified at the thought of IOI taking control of the OASIS. The company’s PR machine had made its intentions crystal clear. IOI believed that Halliday never properly monetized his creation, and they wanted to remedy that. They would start charging a monthly fee for access to the simulation. They would plaster advertisements on every visible surface. User anonymity and free speech would become things of the past. The moment IOI took it over, the OASIS would cease to be the open-source virtual utopia I’d grown up in. It would become a corporate-run dystopia, an overpriced theme park for wealthy elitists.

– from Ready Player One, Ernest Cline

Here, the protagonist (Wade) neatly sets out the main conflict of the book for us. Wade and other “gunters” (egg hunters) like him are searching for clues to a prize that will give them control of OASIS, a virtual simulation created by Halliday.

The corporation IOI wants to find the Easter egg first. Wade values the freedom, particularly the education, he’s gained from the OASIS; IOI values money. The tension is about warring values and visions of the future, not just about Wade winning the race to find the prize.

#2: Have the Potential for Serious Consequences

In some situations, failure is discouraging for your character, but ultimately pretty meaningless: they can try again. But in other scenarios, failure could be one or more of these:

- Hideously embarrassing (e.g. marriage proposal is publicly turned down; character forgets their lines in a school play)

- Career-changing (e.g. massive mistake on a client project; failing to get picked for an elite sports team)

- Physically painful (e.g. getting caught and beaten up; mistiming a jump and falling)

- Life-threatening – or outright deadly (e.g. eaten by a monster; stabbed by a psychopath)

Tension is going to be higher if the consequences of failure are high. We’re not only worried about whether the character will achieve their goal, we’re worried about what awful thing might happen to them if they fail.

Example:

Twelve- to eighteen-year-olds are herded into roped areas marked off by ages, the oldest in the front, the young ones, like Prim, towards the back. Family members line up around the perimeter, holding tightly to one another’s hands. But there are others, too, who have no one they love at stake, or who no longer care, who slip among the crowd, taking bets on the two kids whose names will be drawn. Odds are given on their ages, whether they’re Seam or merchant, if they will break down and weep. Most refuse dealing with the racketeers but carefully, carefully. These same people tend to be informers, and who hasn’t broken the law? I could be shot on a daily basis for hunting, but the appetites of those in charge protect me. Not everyone can claim the same.

– from The Hunger Games, Suzanne Collins

The Hunger Games is packed with this kind of tension from the very start, with a sense that Katniss (the protagonist) and all the people in her community are in a terribly precarious situation. Throughout the book, any wrong move by Katniss could mean death not only for her, but serious consequences for her family and community too.

#3: Create a “Ticking Time Bomb” Scenario

Another great technique for building tension is to put your main character on a deadline. They don’t just have to succeed … they have to succeed before time runs out.

This could be a literal ticking bomb that needs to be defused, but this type of tension applies to any situation where there’s increasing time pressure on your characters. Maybe, after a series of mishaps, they need to catch the very last possible flight to make it to their wedding on time. Or maybe they’re trapped in a submarine and the oxygen is fast running out.

Example:

Hours later Ransom understood what was happening. The Moon’s disk was now larger than the Earth’s, and very gradually it became apparent to him that both disks were diminishing in size. The space-ship was no longer approaching either the Earth or the Moon; it was farther away from them than it had been half an hour ago, and that was the meaning of Devine’s feverish activity with the controls. It was not merely that the Moon was crossing their path and cutting them off from the Earth; apparently for some reason—probably gravitational—it was dangerous to get too close to the Moon, and Devine was standing off into space. In sight of harbour they were being forced to turn back to the open sea. He glanced up at the chronometer. It was the morning of the eighty-eighth day. Two days to make the Earth, and they were moving away from her.

‘I suppose this finishes us?’ he whispered.

‘Expect so,’ whispered Devine, without looking round.

– from Out of the Silent Planet, C.S. Lewis

Right at the end of Out of the Silent Planet, the protagonist Ransom (and the antagonistic characters Devine and Weston) are returning to Earth from the planet Malacandra, with their 90 days’ worth of air running dangerously low. The tension is high, and we’re not certain they’re going to make it. As they’re finally drawing closer and closer, disaster strikes: due to the position of the moon, they need to alter their course. Time was already short, and it now looks almost impossible that they’ll survive.

#4: Design a Clash of Personalities

Tension can often arise from two characters who simply don’t get along. Something about their personalities means they’re quick to annoy one another.

Perhaps one character is cheerful and lighthearted, and the other finds this kind of levity intensely irritating. Maybe one is very outspoken and straightforward, and the other is more guarded.

This type of tension is often present in romance novels, but you don’t necessarily have to use a clash of personalities for a will-they-won’t-they scenario.

Example:

Back on Earth Zero, I go straight to my floor after changing into my office clothes. Dell stands out tall in the herd of desks, more than two-thirds of them empty now. Her face is all tight because she’s been kept waiting by the only person who ever dares inconvenience her.

“Slumming it, Dell? I thought coming below the sixtieth floor gave you hives?”

She smiles, less like she thinks I’m funny and more like she wants to prove she knows how.

“I’ll survive.”

– from The Space Between Worlds, Micaiah Johnson

There’s plenty of tension in The Space Between Worlds between the narrator, Cara (who can be a bit of a maverick, confrontational, and likes to feel that she matters to Dell) and her boss Dell (who is very much by-the-book and comes across as quite buttoned-up). The tension between them is significant to the story, and it helps keep the scenes zipping along fast.

#5: Sew Conflict Between Two Characters

Conflict between characters can be a big source of tension, particularly if you let that conflict gradually simmer away. Readers will pick up on the first seeds or hints of conflict and wonder whether it’s going to build and come to a head.

Example:

‘The thing is, Chelle,’ Dean said, without looking at her. ‘She doesn’t look like me. Donna, I mean. So…’ He let the thought hang in the air.

‘I know! I’ve told you this before. She doesn’t look like me either,’ Michelle countered, her voice tight with frustration. ‘That’s the point. She’s not our baby. Or at least, I’m not sure she’s ours. But that’s not the same as people thinking that she’s mine but not yours. That would mean that I had a thing with some other bloke and I didn’t. I wouldn’t.’

– from In a Single Moment, Imogen Clark

In a Single Moment revolves around two mothers, Michelle and Sylvie, who gave birth to two daughters in the same hospital on the same day. Michelle becomes convinced that the babies were accidentally switched in the hospital nursery overnight.

After she shares this worry with her husband, Dean, he scrutinises baby Donna, decides she doesn’t look like him, and begins to suspect that Michelle has had an affair. This growing tension and distance between Michelle and Dean helps propel the story forward (especially as the central question of the story – were the babies switched? – isn’t answered until very near the end).

#6: Hint That Something’s Wrong With (or Between) Your Characters

Another type of tension is when the reader is increasingly worried about a character, or about the relationship between two characters. Perhaps the protagonist’s best friend is acting weirdly, and the protagonist doesn’t know why. If the behaviour escalates, the tension will too, until we get answers.

Example:

Aidan waved frantically, his teeth gritted together, but his eyes were pretending to be carefree. ‘Leish,’ he shouted, a smile plastered on his face. Aleisha’s heart started beating double time as she soaked up Aiden’s nervous energy – he kept tapping his feet constantly as though he was trying to hold his energy at bay. ‘It’s Mia! She asked if you wanted to hang out.’

‘Yeah, nice idea, would love to,’ she gabbled, trying to catch her breath. ‘Although I’ve got to help Mum with some stuff.’

She shot a look at Aidan. His eyes were red-rimmed, as if he hadn’t slept in weeks. They were darting everywhere – at his watch; at his steering wheel; at his sister, her friend; and back up at the house too.

– from The Reading List, Sara Nisha Adams

Aidan and Aleisha’s mum is mentally unwell, putting a lot of pressure on her children (Aidan is in his 20s and Aleisha is 17). It’s been clear that Aidan’s done the brunt of caring for their mum over the years, but increasingly, he’s been phoning Aleisha and asking her to come home urgently because he needs to go to work.

As readers, there’s a lot of tension here: is Aidan unwell? Taking drugs? Under some kind of additional pressure Aleisha doesn’t know about?

#7: Let Your Character Do Something Unwise

Tension builds when we’re expecting something bad to happen … so one way to create tension is to let your character do something that, as readers, we’re pretty sure is a bad idea.

That doesn’t necessarily need to be something wrong or unkind. It could be something your character does with good intentions, but that looks set to make a situation worse.

Example:

‘It’s Martin,’ Julie says.

‘Martin? Your Martin? Is he with her?’ Kirsty asks. She makes the word ‘her’ sound like the worst kind of insult.

‘No, he’s with his mate, Jamie. Oh my god, what are the chances?’

I turn, then, and have a proper look at him. He’s not bad-looking. He’s just very ordinary.

‘I’m going over there,’ Julie says. ‘I can’t spend all night hiding, can I? Better to pre-empt it.’

None of us says anything, and she gets up and goes. I’m impressed with how decisive she is.

We watch them in silence, trying to be discreet. He’s clearly surprised to see her, but he gives her a hug that seems warm.

‘What do you think?’ Kirsty asks. ‘Good news or bad news?’

‘She wants him back,’ I say, ‘She’s always mooning about. And you can’t get back with someone without seeing them, can you?’

Kirsty narrows her eyes at me, as if she thinks I might have had something to do with this but she can’t quite work out what, and I just smile politely and ask if she’s ready for another drink.

– from The Last List of Mabel Beaumont, by Laura Pearson

Mabel has orchestrated going to the pub on a night when she knows Julie’s husband, Martin, will be there. She’s trying to get Julie back together with Martin … but as readers, we have a lingering sense that Mabel is perhaps interfering where she shouldn’t.

All of these different techniques are great ways to add tension into your story (or to increase the levels of tension that are already there).

It’s important to keep your genre in mind. All stories will have some kind of tension to keep us reading and engaged … but if you’re writing, say, a horror novel, you’re going to have a much higher level of tension than in a sweet romance.

You’ll also want to think about how tension plays into both the internal conflict and external conflict within your novel: check out internal vs external conflict for more on each of those.

What types of tension could you experiment with in your novel or short story? Are you going to use one of the ideas above – or try something different? Let us know in the comments.

About

I’m Ali Luke, and I live in Leeds in the UK with my husband and two children.

Aliventures is where I help you master the art, craft and business of writing.

Start Here

If you're new, welcome! These posts are good ones to start with:

Can You Call Yourself a “Writer” if You’re Not Currently Writing?

The Three Stages of Editing (and Nine Handy Do-it-Yourself Tips)

My Novels

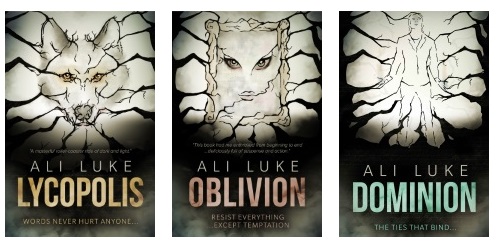

My contemporary fantasy trilogy is available from Amazon. The books follow on from one another, so read Lycopolis first.

You can buy them all from Amazon, or read them FREE in Kindle Unlimited.

I’ve read stories where I thought the main character did things that were so stupendously stupid I quit reading. One that springs to mind involves a guy who asks a woman out three times and stands her up each time. Largely because he was too self absorbed to set a reminder on his phone. I wondered why I wanted to read more about this stupid jerk, and decided I didn’t.

The main character doing something stupid isn’t always a good thing.

Good point, Jay — thanks for adding it! I absolutely agree. I think characters can do things that we, as readers, feel are unwise or dangerous … while the character’s motivation is still understandable to us.

Characters who just do stupid things for the sake of the plot are going to annoy the reader (and I do think authors need to make sure they’re answering all readers’ implicit question “why should I care about this character”).